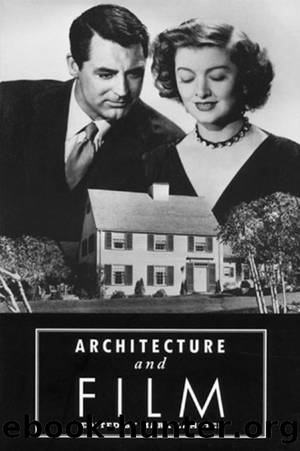

Architecture and Film by Mark Lamster

Author:Mark Lamster

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Princeton Architectural Press

Published: 2012-08-29T00:00:00+00:00

In 1959, Saul Bass ran the title of Alfred Hitchcockâs suspense thriller North by Northwest across the gridded facade of the United Nations Secretariat Building.

OPENING CEREMONIES:

TYPOGRAPHY and the MOVIES,

1955â1969

PETER HALL

IT MIGHT SEEM perverse, to the film critic and student, to decapitate the centuryâs films of their opening and closing minutes and contemplate the offcuts as a movement. But this ignoble assortment of clips yields a colorful field of study. In a sense, the film title is to the movie as the billboard and neon sign are to architecture. It advertises the filmâs wares; reflects, or betrays, the director and studioâs aesthetic aim (or lack thereof); and with the aid of hindsight indicates something of the prevailing state of the film industry. And like the sign, the title sequence is either ignored or disparaged by serious film students for its suspiciously utilitarian motives and close relation to advertising. Their qualms are not entirely unfounded. The stand-alone credit sequence came about as the products of vanity and the unexpected union between filmmakers and commercial artists. But as a form, it is capable of reaching sublime heights. It might be considered the beautiful bastard child of the medium.

The film title came of age in 1955, when director Otto Preminger unveiled his noirish junkie-thriller The Man with the Golden Arm with a striking monochrome graphic sequence designed by Saul Bass. To Elmer Bernsteinâs syncopated score and big-band orchestration, a series of white bars appear and shift on the black screen, suggesting drumsticks, then searchlights, before finally transforming into the jagged arm of the filmâs title. Bass called it âa sort of abstract balletâerratic and strident.â1 At the time, this kind of prequel was unprecedented. Credits bearing the names of the movie, director, studio, and stars (not necessarily in that order) were usually rendered by lettering artists and held up unceremoniously in front of the camera at the beginning and end of the feature. But in The Man with the Golden Arm and, to a lesser extent, Carmen Jones a year earlier, Preminger and Bass turned this static procedure into an animated event. According to Bass, âthere was a time when titles were very interesting, going back to the early 1930s or even the late 1920s. Then it bogged down and became bad lettering produced by firms that ground out titles. What I did was reinvent the whole notion of using a title to create a little atmosphere.â2

The motive was undoubtedly commercial. The stark power and reductive formalism of The Man with the Golden Arm sequence was actually derived from Bassâs previously designed poster for the film, which encapsulated in a simple âideogramâ the story of an addicted jazz drummer (played by Frank Sinatra) caught in a triangle of dependency. Rather than illustrating the ingredients of the storyâa drum set, urban scene, and distraught faces of the stars would have been acceptableâBass devised a logo with an arm thrust downward into a prison of black rectangles. It was a seminal example of his ability to

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Kathy Andrews Collection by Kathy Andrews(11793)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(8947)

Spare by Prince Harry The Duke of Sussex(5165)

Paper Towns by Green John(5163)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(5065)

Industrial Automation from Scratch: A hands-on guide to using sensors, actuators, PLCs, HMIs, and SCADA to automate industrial processes by Olushola Akande(5038)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4280)

Be in a Treehouse by Pete Nelson(4017)

Never by Ken Follett(3917)

Harry Potter and the Goblet Of Fire by J.K. Rowling(3834)

Goodbye Paradise(3790)

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro(3376)

Into Thin Air by Jon Krakauer(3369)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3352)

The Cellar by Natasha Preston(3315)

The Genius of Japanese Carpentry by Azby Brown(3277)

120 Days of Sodom by Marquis de Sade(3245)

Reminders of Him: A Novel by Colleen Hoover(3061)

Drawing Shortcuts: Developing Quick Drawing Skills Using Today's Technology by Leggitt Jim(3057)